This site is all about old, antique (vintage if you’d prefer), Farm Tools and associated equipment.

My collection of farming bygones began back in the early 1990s, a chance encounter with an old girl friend of some twenty five years previously led to the establishment of

The Percy Jones Collection

That was the name of her father, a man steeped in the traditions of Welsh hill farming and a hard way of life begun in the days of the First World War. Born in 1912, Percy was one of four children brought up on the small farm called ‘Y Talwrn’ which is in the hills of the Cambrian mountains between the villages of Llanwrthwl and Elan, a few miles south west of Rhayader in Powys. Being west of the Wye and south of the Elan river the farm is in the old county of Brecknockshire, now a part of Powys. In truth the area is more akin to the neighbouring county of Radnorshire in its long traditions and dialectic mannerisms. Architecturally too the area has close association with the building styles and material content of the hill farms of Radnor.

Farming in the early twentieth century was not vastly different to the previous century; small flocks of sheep and some beef cattle, a pig or two, poultry and of course horses, were the mainstay of the unit. A few milking cows and an Ox were usually also present, the former to provide milk and cream for making produce, the Ox for draught work on the farm. The great Shire horses of England were not present in those wild upland areas but by the start of the eighteenth century more and more horses, probably of the ‘Cob’ type or hardy mountain ponies, were being used instead of an Ox. However, teams of Oxen were still being used as late as the 1960s.

Tractors began to make their presence felt in the 1930s with early Ferguson Brown, Fordson and imported makes from the United States such as Allis Chalmers, McCormick and Case. Few farms in upland Wales could afford the investment in such equipment and no doubt there was a little scepticism as to the real advantage of such machines. It was not really until the immediate post war period that tractors became a common sight although the trusty (but terribly annoying !) Standard Fordson model ‘N’ had been regularly seen on farms during the war years.

The arrival of mechanisation was to change one face of farming forever but in the uplands the other ‘side of the face’ remained locked into a centuries old tradition where hand labour was still the mainstay of the farming operation. Thus it was that tools and implements that had hung in Tudor barns were still in use while the dark clouds of another World War clouded the horizon. But the days of the farm labourer and his trusty tools were already closing, indeed ever since the arrival of the industrial revolution the drift away from the countryside of old was continual. In the rural uplands of Wales that drift was inexorably toward the valleys of South Wales and the cities of England. Many were the Welsh speaking miners of the Rhondda who’s heritage lay in the small homesteads of the Cambrian mountains or the tyddyn landscape of Cardiganshire. Many too were the milk-men of London and the maids of the grand Victorian houses who made the long trek eastwards, often accompanying the great cattle droves as the Drovers took their beasts to the markets of the city.

I was hardly knowledgeable about my own Welsh heritage except that I knew half of my father’s parents had been miners and the other half farmers. As for my mother’s side, her mother’s family hailed from the Cotswolds and had come to Wales to be lock-keepers on the Monmouthshire canal at Five Locks in Pontnewydd (now consumed within the post-war new town of Cwmbran). My maternal grandfather was a Black Country man, a mining engineer who was a very keen cyclist in the early year of the twentieth century. He’discovered’ the ‘green and pleasant land’ of Gwent on such a long distance ride. Returning to the depressed area of his hometown he persuaded the whole family to set off on the long three week walk to Pontnewydd and there they settled.

I grew up along the banks of the old disused canal, rich in wildlife and freedom. Holidays were spent in Carmarthenshire, in the fertile dairy lands of the Towy valley where I came face to face with the realities of farming life. The relationship with my Sennybridge girl came in the late 1960s and soon my holidays were spent helping out on her farm with her ‘time-warp’ father and his ‘traditional’ ways of doing things.

By the time we met up in the early 1990s I was a dry stone waller (see my Welshwaller’s blog) and had become very interested in the ways of both traditional farming and conservation. I had already begun to gather some old artefacts of bygone farming, mainly that which I came across in my work, such as old ploughshares and large horse shoes, or in the old derelict buildings of farms I visited. The news that Percy had died and that all his tools and equipment were to be’thrown’ was both appalling and exciting. To cut a long story short, I took it all home with me thus saving his daughters the problem of disposing of it all.

I have to say that much of what I retrieved was an absolute mystery to me. Rusty old spikes and forks, worm riddled handles and strange shaped iron filled my shed but gradually I learned about them. I soon realised that what I had – albeit minus quite a few items which had gone astray for various reasons – was an example of what every upland farm would have had for the previous two centuries and probably much longer.

I began to research the names and uses of the hand tools, I became an avid ‘listener’ to old farmers and their wives as I attended shows with my small collection. Soon those same farmers began to give me items which they themselves had used but which had lain unloved in their own barns and sheds. Before long I realised it was behoving on me to record those memories as, before very long, there would be no-one left to tell the story of farming in the Welsh uplands.

So, here we are, some twenty five and more years later and my brain and my barns are overflowing with the artefacts and stories of a hundred years and more of farming memorabilia. I’m sure there are still many of my friends and family who stifle an involuntary shake of the head when I arrive with yet another piece of rust in my car or they find me in the kitchen polishing a tool handle or waxing some strange metal object. But just as they are bewildered by my passion for these bygones there are now many folk who regard me as a an item of interest and a repository of information. “You should do a book”, is something I hear often; “Thanks you SO much for a fascinating talk”, is generally the response to an evening presentation in a village hall in a remote valley in the hills. This is my response, I will attempt, through this latest series of blog posts, to show and describe the multitude of items that now make up the ‘Percy Jones Collection’.

As my interest gathered pace and the items ‘came out of the darkness’ of years of neglect and abandonment I found that some items held sway over my psyche. Now I don’t want to get ‘coming over all sentimental like’ nor even spiritual but there’s no doubt that handling an old item – and I imagine that applies whatever the particular field of interest – which was once treasured and worked hard by its owner, does affect me. “What stories they could tell”, is the oft spoken response by folk who view and handle those items at shows and talks and indeed that is precisely the reaction I have. I am often fortunate enough to actually know what stories they could tell because the very person who made or used the item gave it to me or it was used by their parents or someone they knew well. The most thrill comes from the discovery of an old tool in a derelict homestead or in a hedgerow, left behind on a day never to be known and in circumstances which could generate a whole series of country novels.

There are certain tools to which I am always drawn – and for which temptation generally overcomes my better judgement ! There’s no doubt that wooden items draw me to them especially if they are of an ancient design. I think that there is within most folk of a rural heritage – consciously or sub-consciously – a ‘feeling’ for wood. By wood I mean the native wood of our ancient forests. The ash, beech, oak and sycamore which abounds in the uplands of Wales, the chestnut and hornbeam and the now extinct great elms of England and the native birch and pines of the Scottish highlands. The shrubs of our woodlands and hedgerows such as hazel and holly, spindle and alder and the many species of willow were also highly prized and valued. I have no idea what that draw relates to, it is locked up in my DNA, perhaps it is locked up in all our DNA but circumstances or the alignment of the stars have to be just right to release it. Whatever it is, it is powerful and manifests itself in stacks of ash and hazel poles, in lengths of interesting cordwood and dozens of strangely shaped lengths of many species hanging to season in a barn. Yew is a favourite, holly I adore, beech often comes home with me and a hazel rod which has been dominated by a coiling ivy always gets my attention. I have no idea what I’m going to do with them, I am no artisan crafts-person nor am I a very accomplished carpenter woodworker. There is something about wood and woodlands that soothes my soul.

Having spent nearly half my life in a manual occupation I can look at the old implements and tools of agriculture with an understanding and an empathy for the toil and tribulations associated with their use. Wrapped in shabby old garments that hardly passed as waterproof, men walked the road to the churchyard behind ploughs and hoes, behind heavy iron and creaking harness. Their road was much shorter than mine and few of those old countrymen saw their own three score years and ten. It is only through hard manual labour that the mechanics of the human frame can truly be understood, it is only through sweat and toil and the overcoming of that inner voice that calls for a halt, that a person learns about themselves and others. Thus to see an old breast plough (or ‘cock-spade’ as northerners know it) the graft that it represents is clear to all. To hold and wonder at the ergonomics of a peat slane is to wonder at the diligence of folk to go out on the moors and cut their own fuel, turve by turve and carry it home so as to survive another winter in the harshest of environments.

Breast plough or betting/betling iron or cock-spade

Peat slane and marking iron for cutting turf/peat

Few are the folk that know these tools today; the breast plough, though widely found in all the upland areas, is way past its ‘tell-by date’ and it is ten years and more since I met someone who knew what it was let alone remembered it in use. Similarly with peat cutting tools, very specific yet very general in design and use, although I did come across a farmer at Fryup in the North York Moors a year ago who still used the tools of his grandfather and father to cut his annual allotment of peat – albeit today it is brought home on pallets stacked on a tractor-pulled trailer. He remembered his folks hand-barrowing the turves across the boggy moor to the road and there loading it onto a cart pulled by an ageing horse. My old neighbour from Abergwesyn remembered well the peat cutting and those that did it but even he did not recall the betting iron in use.

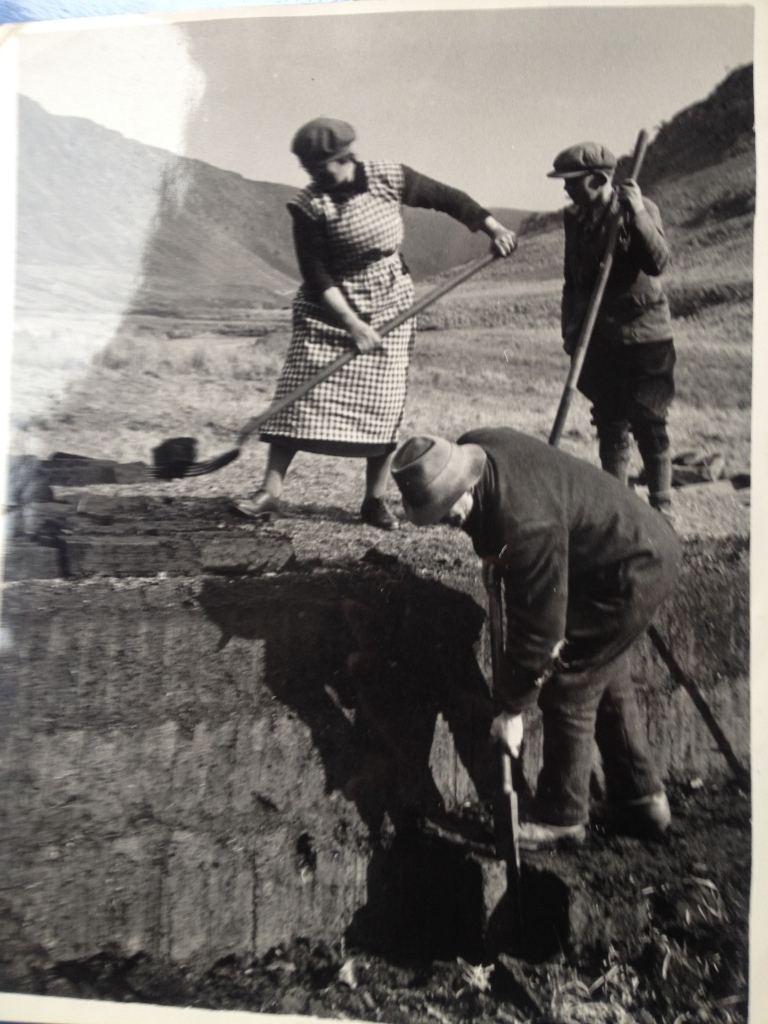

These folks are cutting peat near the ‘Devil’s Staircase’ on the old Tregaron to Abergwesyn Drover’s road in north Breconshire in the early 1920s. The girl is Nano Jones with her brother William, later of Llanerch y Cawr in the Elan Valley, together with their father, Will, who farmed at Llanerchyrfa.

There are still a few folk alive in those remote hills of the upper Tywi and Irfon valleys who remember the smokey peat fire that never was allowed to go out. What I find most astonishing about the great peat bogs that blanket much of upland Britain and almost the whole of Ireland, is that it was all laid down in a very short period of about 2 thousand years starting around six thousand years ago – in other words, when hunter-gatherers were already beginning to farm and settle the land. They came about as the result of a climatic change which saw temperatures rise and rainfall increase significantly.

I visited the Orkneys a few years ago and saw a ‘blackhoose’ at the Kirbuster museum where they still kept the ‘home fire’ burning. On the North York Moors, at Wild Slack farm (a great little camping and caravan site should you ever find yourself that way) Martin Foord showed me the varying colours of the peat which denoted its calorific value and determined which was used for roast lamb and which for oatcakes.

At various times throughout this blog I will narrate happenings around the syndrome known as ‘it’s a small world’, this is one of them. I had long wanted to visit the North York Moors and found myself nearby in the autumn of 2016. I was working on a canal restoration project at Pocklington, east of York. Knowing I would be in the area for some six weeks I took along my camping gear and ventured off northwards. My guide-book was a wonderful anthology of traditional life in the North -East of Yorkshire by two intrepid ladies, Marie Hartley and Joan Ingilby (published by J.M. Dent, 1972). On page 75 they describe the peat cutting activities of the moorland farmers and include several quotes from named farmers. Imagine my astonishment when arriving at Wild Slack and talking to Mr Foord about my interest and my ‘guide-book’, he said “oh, my father is mentioned in that book”, and there he was, Robert Foord, telling how and why some peat cutting spades had the wing on the left and some on the right; it depended on whether the cutter was right or left handed ! Of course it did.

Well, despite the snow, Spring is trying its best to ‘spring forth’. I have begun to think about my plan of action (in terms of restorations) for this year: there are a couple of carts that urgently need attention, there’s a Living Van to complete and several dozen hand tools to attend to – the ever-present wood-worm will get them if I do not keep ahead of the pesky critters !

With Blessings across the air-waves on this Easter weekend, ‘Old Lob’* signs off for now !

*My ‘nom de plume’ comes from a memory of the very first school book I can recall, it fascinated me even then, the story of an old farmer and all his animals. Old Lob sowed the seeds of my fascination and love of the countryside, it must have been well known in the family for I was soon given the ‘nick-name’ (by uncles and aunts) of ‘Percy the bad chick’, himself a notable character in that fable – small world isn’t it !