I live in an area dominated by sheep farming and hence it is not surprising I have acquired a large quantity of items related to the management of those animals.

Shearing is one of the major activities and labour saving devices evolved throughout the twentieth century. The clipper shears were and still are, extensively used and it is still in living memory that whole flocks (albeit relatively small flocks by today’s standards) were shorn using the hand-held device. By the early twentieth century a hand-cranked shearing unit became available. Companies such as Lister, Wolseley and Stewart produced versions which gave mechanical drive to the clipper head via a cable similar to a speedometer cable; an outer flexible tube in which sat a square drive cable. At the drive-end a pair of cogs which interlocked when in use and sent the horizontal drive from the gearbox – in the case of the small unit produced by all three companies or from the chain drive of the larger toothed wheel machine.

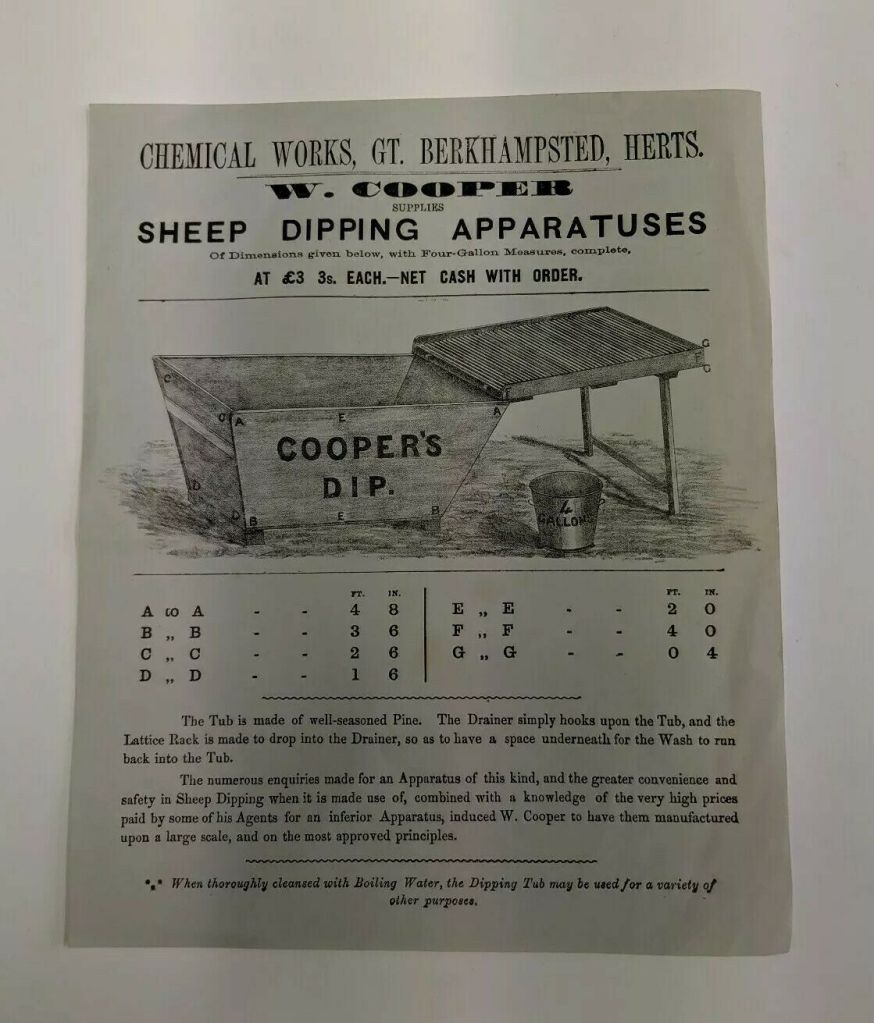

The wooden portable sheep dipping tub is quite a rarity. The firm of Coopers produced the very toxic dip solution which was commonly used throughout the world.

I have quite a number of sheep related items, from hand shears to mechanical shearing devices. The top photograph shows a Lister hand cranked shearing machine and a Stewart ‘Ball’ machine both from the 1920s era but which were still being used up to and including the 1960s.

In the small upland farms where flocks were rarely in the hundreds, hand shearing prevailed despite the ready availability of both hand cranked and engine driven shearing machines. The method varied according to area and preference. The ‘shearing bench’ was a more comfortable method whereby both shearer and sheep were sat on a long wooden bench although in the photograph from Lloft y Bardd in Abergwesyn in northern Breconshire both shearers are standing whilst the ewe is raised on the bench. Often, particularly in a large shearing where several men were clipping at the same time, the sheep were ‘sat’ on the ground and the men bent, awkwardly, over them. It was noticeable that many of the old shearers I met had pronounced ‘hunched’ shoulders and backs.

The early type of shears (at right in the above photo) were rather like large scissors. This pair came from an old Radnorshire farm on the edge of the English border near Kington and may therefore have heritage from that foreign clime. They are heavy solid brass and a blunt arm so as to avoid stabbing the flesh. A similar type of shears can be seen carved into the medieval oak door of Burford church in the Cotswolds. The more usual and common sprung shears come in various styles and sizes although all within a small range to maintain their ergonomic efficiency and allow speed and durability of both edge and shearers grip !

The common shearing bench in Wales was a simple plank type which had other uses at different times. In the north of England a more stylised bench which gave a wider platform on which to sit the sheep was preferred. My own example from the Lake district is recorded as being used on the same farm for over a hundred years and is one of my most treasured items.

Shearing bench typical of the north and Scotland. Lake district circa 1820s.

The evolution of the shearing process was given swift and technical progress once stationary engines began to be cheaply available in the 1920 and onwards. The foremost company was arguably Listers of Dursley although many engine manufacturers also developed shearing attachments for their products. My collection has several such adaptions although they are all Lister products. My engine driven double shearer from that ubiquitous company is the famous and mass produced Lister D. It is of 1935 vintage and spent its life on a Breconshire farm near Trecastle.

The firm of Listers, based in Dursley in south Gloucestershire, was one of those pioneer industrial engineering companies in which Britain excelled in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth. They were still manufacturing in the 1960s. I have so many items in my collection made by Listers and the sheep management items are but a small section but my Lister Number 1 hand shearer, with the large bicycle type chain driven wheel cranked by a wooden handle was one of the first items I acquired and remains one of my favourites.

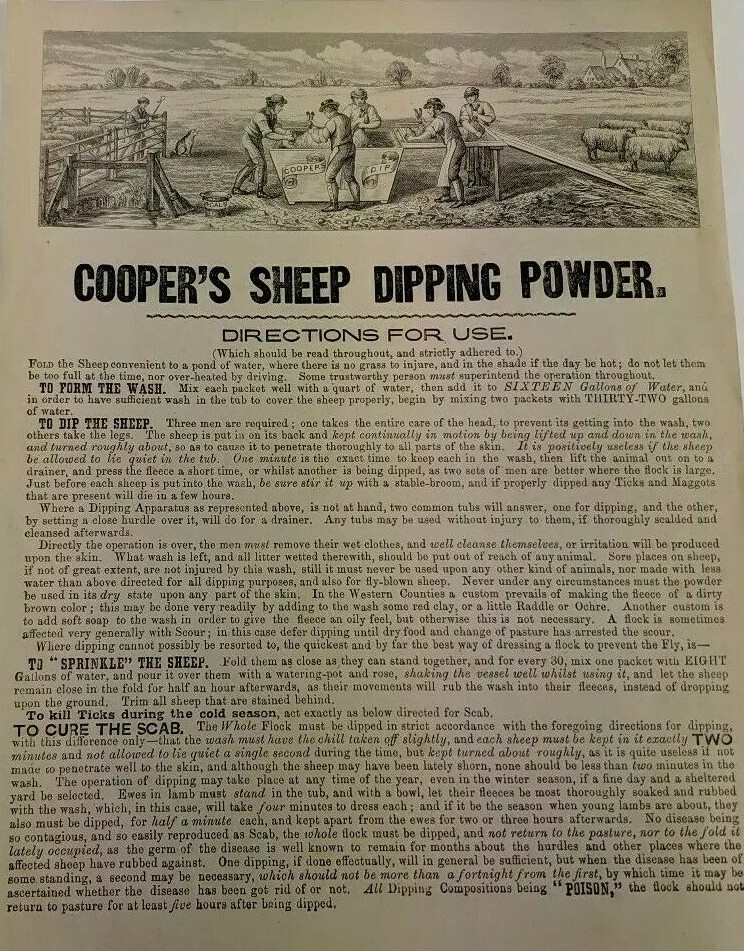

The medicinal treatments vary from dosing via a mouth infused potion to total submersion in a tub of toxic chemical solution to kill various infectious ailments such as lice and scab. The wooden portable tub mentioned above was quite rare, more commonly whole flocks were dealt with at a tipping tub. In the preparation for shearing the flock were dunked in clean water, usually at a specially constructed site in a mountain stream. This mostly consisted of a dam of stone construction which could retain a good depth of water, the sheep needed total immersion. The process required plenty of helpers, to catch, throw in and stand in the cold water to make sure the sheep got a good bath.

The dipping tub was either an ‘on-farm’ tub or a communal tub with an adjacent fold where flocks could be sorted and separated. Either way it was necessary to ensure a good total immersion. In the not too distant past it was necessary to have a policeman in attendance to confirm the process was carried out correctly and at the required time.

To assist in ensuring the sheep went right under, a long handled crook (w Pren dippo) was used. These were mostly home made items but firms such as Coopers supplied them free of charge with the purchase of dipping solution and manufactured examples made of metal became readily available after the 2nd World War.

The ‘dipping’ of sheep originally referred to the practise of washing them in a river pool, often a temporary creation formed by a removable dam structure. In the upland areas these ‘wash pools’ were often a dry stone construction with an attached stone fold to accommodate the waiting animals. Several hundred were often dipped at a communal gathering where all the farming families would co-operate to get the job done. Several men would spend the day in the cold water making sure the fleeces were thoroughly cleansed.

In the days before chemical disinfectants (County wide ‘compulsory dipping orders’ began to appear in the early years of the twentieth century), that is right up to the First World War and in remote areas, sometime after, the process of ‘salving’ took place. At the beginning of October each animal was man-handled onto the bench and its wool was systematically parted to reveal the skin onto which was smeared a greasy paste made up of tar (generally Stockholm’), fats, often rancid butter, oils and usually some home-mixed potion the ingredients of which were a closely guarded handed down secret ! At present a ‘salving bowl’ is missing from the collection (hint, hint!)

Once washed and then sheared the sheep needed to be dosed with both external and internal parasite preventatives. Dipping in a ‘not nice’ chemical solution was again a communal effort, in many upland areas until well into the 1970s. It is one of the paradoxes of the efficient treatments of twentieth century farm medicines that so eradicated, for the most part, the lice and scab that so beset the hill flocks, that many a farmer fell ill to the undetected side effects of the organophosphates used in the processes. Severe debilitating illnesses of body and mind still linger on in the older generations who were exposed to the agri-chemicals, many more left this life by their own hand unable to deal with the disabilities inflicted upon them. It is a shameful aspect of governmental control and responsibility that the farming communities were never given the recognition of the causes and effects of what were in effect, industrial illnesses; no different in their calamitous outcomes than those which affected the mining industry, the slate industry and the asbestos industry.

Almost all upland farms, throughout the land, relied on access to open hill grazing. Generally these were called ‘the hill’, the common. the mountain or here in Wales, the mynydd. Nowadays it is generally assumed, by non Welsh speakers, that mynydd means mountain. Whilst the mynydd is more often than not, a mountain, in reality the old use of the term related to the open ‘common’ grazing of the township or tref, which is to say an area of hamlets and dispersed farmsteads. Within a defined geographical area certain ‘commoners’ and ‘homagers’ had rights to carry on specific activities on the common land – the land was ‘common’ to those folk. It must be realised that it is NOT the case that commons belong to those entitled to make use of it. Neither is it the case that NOBODY owns it. Much of what is deemed common land is in the ownership of the government or local authority bodies which today includes National Parks and increasingly large private companies and charities. The ownership of these large uplands originally and remains the case in many areas, is vested in long standing large estates. These historic entities have their origin way back in medieval times and the commoner’s rights too are ancient. During the early industrial revolution many successful entrepreneurs bought up those earlier estates and thereby gained access (or so they thought) to the upper echelons of society.

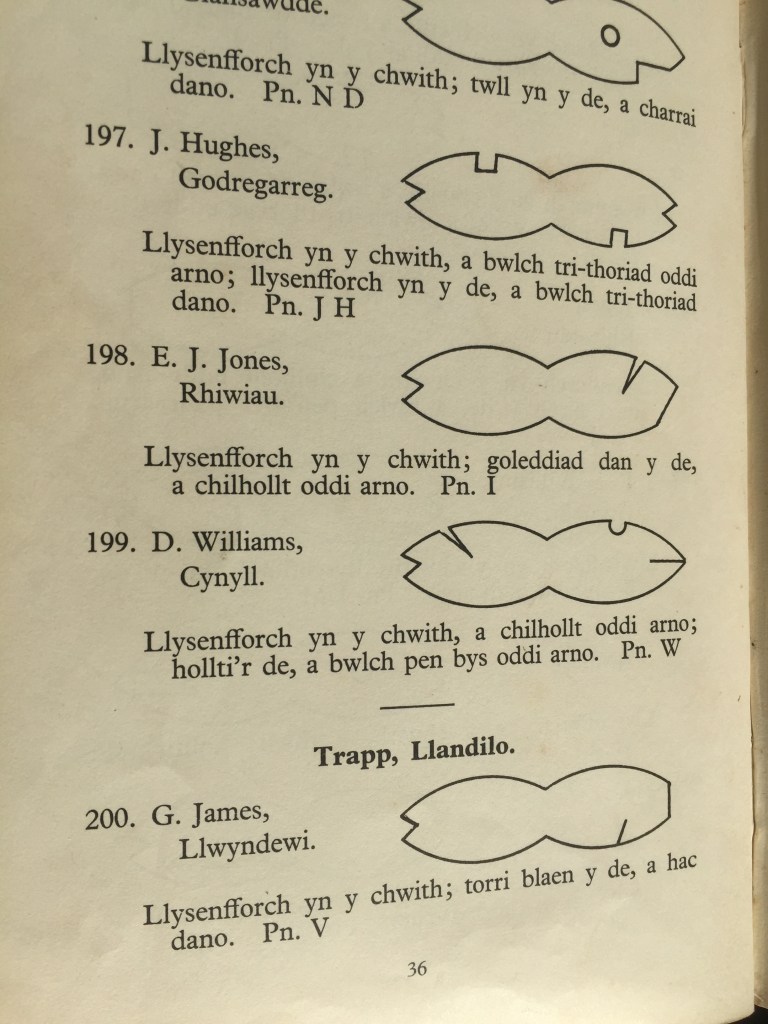

We are left today with farms (and still some cottagers) which have the right to turn an allocated number of animals to the common. Generally that mostly means sheep but many still retain the right to turn cattle and horses out also but few do. Each flock has to be identified and each animal therein must be individually permanently ‘branded’. The two traditional methods of marking was a lettered brand, which on sheep was a ‘pitch’ painted emblem placed onto the skin after shearing. This long established mark stays with the flock even if the farm to which it belongs gets sold and the rights taken by another person. Thus it can be the case that a particular enlarged farm has more than one flock mark. These ‘branding’ irons have an important history and are generally valued by the descendants. Several have been donated to the collection and are cherished items.

In addition to the letter code, which would inevitably fade and become hidden as the fleece grew, an ear mark was cut into the poor lamb. This flock mark was intricate and carefully carved so as to be unmistakable. For each ‘common’ a book was (the most recent for my area was 1968) published showing each mark and identifying the owner together with the allocated right i.e. how many animals that farm is allowed to have out on the common. Today as well as the traditional ways of marking individual animals, each has a plastic ear-tag which is clipped into a hole in the other ear (the one without the cut-out flock mark). This tag has an identifying number which is recorded by the farmer and ‘Big Brother’. In some instances a computer-readable chip is forcefully ingested into the animal. This ‘bolas’ remains inside the animal and is read by a hand-held scanner.

If the farm’s rams or indeed the ewes had horns a branding iron was used to burn he mark into the horn. The smell of a burning horn is one of the most unpleasant farm odours.

The large mountain commons extend over many hundreds of square miles and are parcelled into Graziers Associations each of which has a defined area in which their animals are supposed to graze. Back when ‘shepherds watched their flocks by night’ the animals of a particular farm stayed in their allocated patch or ‘heft’ (in Wales ‘rhesfa’). Today that is rarely the case and sheep can often be found many miles from where they are supposed to be. There are literally hundreds of ear marks in the book for my area each with such subtle variations as to be indiscernible to the untrained eye. I am in awe of a neighbour, a hedger by trade, who is acknowledged as the man who knows each mark for the whole vast mountain !

The flocks in the past had another identifying appendage. On the often cloud covered hills and the mist shrouded Wolds, flocks are difficult for the shepherd to see or locate so a bell was hung around the neck of the flock leader. This animal was usually a ‘wether’ which was generally hand reared and thus more likely to come to the shepherd (thinking treats were at hand !). This ‘Bell Wether’ could remain in the flock for some years and was an excellent aid in bringing the flocks to the shepherd.

A couple of ‘cluckett’ sheep bells from the hills of north Ceredigion.

On the old open Wolds of England (Cotes Wold means land of the sheep) it was customary for a shepherd to have a ‘ring’ of bells attached to several animals in his flock and the melodious clang and clank of the cluckett and the rumbler echoed across the windswept hills.

I have had a long attachment to the lives and tools of the old shepherds of the Wolds reaching back over fifty years and will produce a post specifically about the items in the collection relating to the Shepherds of previous centuries.

The computer age came to us a couple of years ago and an new tracking devise arrived. It had been predicated on the problem of the theft of animals off the hill which of course was only spotted a few times a year when the flocks were gathered for shearing or clearing the hill for the winter months. Some tech-wizard, I believe in Spain, came up with the novel idea of attaching a ‘bell’ to several animals in each flock (goes around and comes around) but these particular bells are silent. Instead of the shepherd having to be out on the hill and listening to locate them he, or more likely ‘her indoors’ (or even more likely – the kids at home !) could sit in the warm kitchen watching the computer screen. A large white satellite dish affixed to the house received a signal from the ether (well Spain actually) which beamed the position of each animal with one of the green bells superimposed onto a map of the vast expanse of the mynydd.

I have to say it was a pretty impressive bit of kit (I think each ‘bell’ cost well into four figures …) and it certainly had the potential to deliver its goals. The main aim was to alert the ‘screen watcher’ to their animals running wildly as if being chased (or rounded-up) wherein the farmer could jump on his horse (sorry, Quad) and race off – the five or ten miles – and interdict the attempted theft. Of course sheep sometimes do just take it into their head to gather together and rush off to another part of the hill. A walker, especially with a dog, on a lead or not, is guaranteed to set them going as is a noisy scrambler or sedate rider. One of my farmer friend’s wife got quite into watching her little green dots; stationary for ages (has it died ?) wandering aimlessly, moving down from the tops (weather ‘coming in’?) following in line up to the higher ground (is it being ‘cowsed’ i.e. slowly ushered?) until she realised it was as useful a tool to detect rustling as riding around in the truck or on the quad. The bright white satellite dishes still adorn the farms, the expensive green bells hand unloved in the shed and the ‘app’ lies dormant hidden in the hard-drive …

Husbandry (amathyddiaeth in Welsh) also involves playing animal doctor, along with midwifery, wet nurse, paediatrician and fostering, which also often requires the skinning of a dead lamb and clothing another – orphaned or rejected – in the skin to fool the original mother that her ‘child’ has been reborn ! There are a variety of specially evolved tools and instruments to aid the famer shepherd in these duties.

One of the big recurring problems for the animals and the farmer relate to the wet climate in which most British, especially Welsh. sheep have to survive. Whilst it is supposed that some of the rare breeds, such as Soay, have been in these climes for several thousands of years, their origins are clearly in more dry and warm parts of the world. Thus there feet, a horned bootie, is susceptible to rot and infection. Like all of us who walk our toe-nails need periodical attention especially clipping. The all-too-common site of a lame sheep betrays the issue. Rot in the hoof occurs in damp and wet land in which the infection lives just waiting for a casualty. Regular paring of the hoof (toe nails if you will) and the application of a disinfectant (normally purple and easily seen) helps prevent and cure. The strong sprung pliers or clippers – not unlike a set of secateurs – was and is a constant on sheep farms.

Whilst today (and for the previous couple of centuries) we are used to seeing large flocks most of which are one or other of the ‘white’ fleece breeds, that was not always the case. Apart from the large monastic flocks which roamed the open hills, the small hill farmer of the medieval and post medieval periods kept small number of breeding ewes primarily for home spinning of the wool and milking the mothers for home consumption. The primary pastoral cash crop was cattle based.

Breeding was of course the annual event of great importance. Without getting too deeply into sheep husbandry (not that I would be able !) suffice to say, for readers unfamiliar and with apologies to those more knowledgeable, lambs arrive in Springtime. Depending on where in the country that can be anywhere from February to May and increasingly earlier. That is partly having regard to the onset of grass growth to assist the ewe in milk production and then the new born nibbler but also to the gestation period following on from the autumnal insemination. Rams are put to the ovulating ewes in the October/November full moon periods.

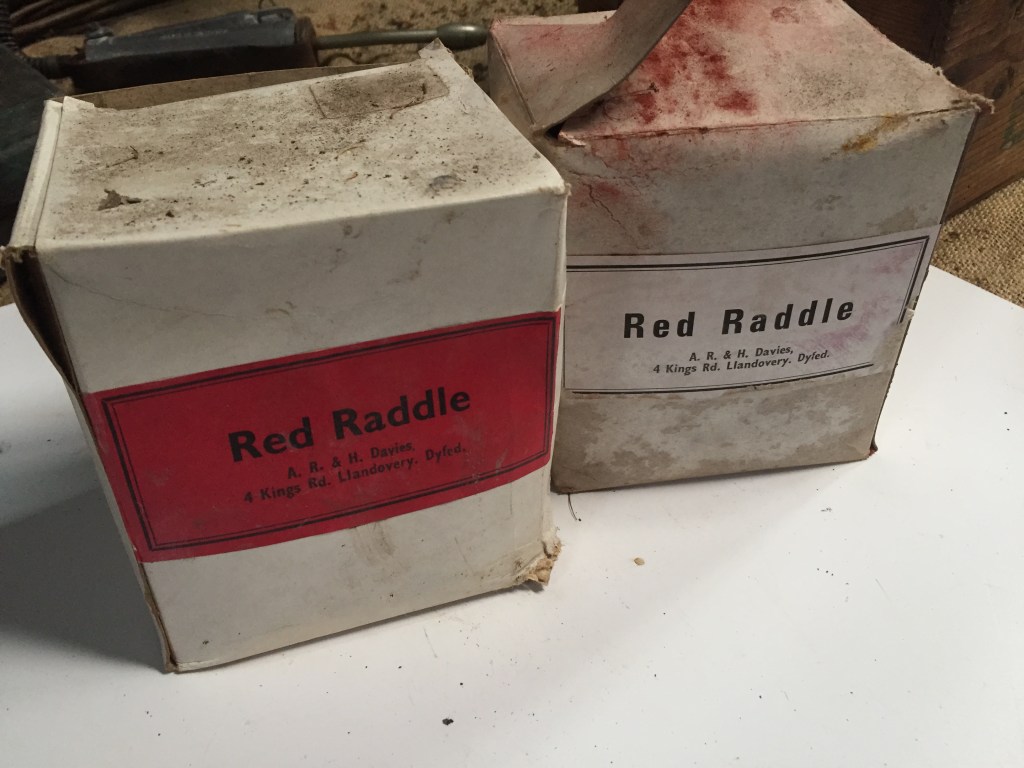

Nowadays mobile scanning of the (hopefully) pregnant ewes takes place to aid the farmer in knowing which ewes are in lamb and how many each one is carrying. However, in order to be sure the ram has been in attendance, the shepherd is given evidence in the form of a red mark on the wool at the rear of the ewes back (i.e. showing the ram has climbed aboard). Known as ‘raddle’ and originally a natural pigment from the eponomous plant, the red powder is mixed into a paste and applied to a block with a felt pad which is itself encompassed in a harness which is fitted to the ram and fixes the pad on his belly such that if and when he ‘climbs aboard’ the red raddle stains the ewe’s wool.

An original harness and box of raddle was kindly donated by a time served local ‘shepherd’.

The lamb has a short life in general. Most see only one summer but some stay on to enlarge the home flock or get sold on to other farms. A very small number of young male lambs get to grow to maturity complete with ‘all their tackle’ in working order. Most young males (of all domestic stock) are castrated soon after birth. That operation can be achieved with a quick swipe of a sharp knife followed by a snatched removal of the testes.

Another method was rather more protracted and no doubt uncomfortable. A clamp could be locked onto the sack to stop the blood=flow and cause the testes to shrivel and die. The pair in the collection seem rather large (6″ long by 3″ wide ) and heavy to be hanging between a poor lamb’s rear legs.

“Leave them alone and they’ll come home, dragging their tails behind them”

But not for very long ! One of the first jobs of the shepherd was, and generally still is, the removal of the poor little creature’s means of showing his mum her milk is flowing. The wriggling jiggligng six inches of white woolly flesh and bone is similarly killed off by ending the blood supply. That is achieved by the application of a tight rubber band using a specially designed spring loaded reverse pliers. I.e. the nose opens when the handles are squeezed closed as opposed to the normal operation of pliers. However, there was a more swift but brutal and painful method which entailed a sharp chisel like metal head on a wooden handle which was heated to seal and purify the wound at the same time as it severed the tail.

From the Tudor period sheep gradually increased in importance as an economic factor in English farming. The upland areas of Wales and other highland zones of Britain continued as cattle pastoralists with the woolly members of the farm’s stock still mainly about meat, milk and local wool spinning. From the post medieval period right through until the present time the economics of sheep farming changed. As the Agricultural Revolution progressed from the mid 1700s, a greater scientific understanding of the ailments which beset the flocks. Chief among those were fluke and scab. Dipping in chemical and the continuing application of salve aided the scab and maggot issue and ‘dosing’ attacked the liver fluke. Squirting a chemical down the throat of the animal kills the the little critter which otherwise causes a slow and long deterioration to ultimate death. An early dosing gun and bladder to hold the ‘dose’ was donated to the collection from a north Breconshire hill farm.

The infection of liver fluke occurs through ingestion from the pasture. The tiny critter hides in the sward and even the stomach acid doesn’t kill the lice hence it goes in, comes out and infects another animal. In the early 1700s it was discovered that the intestinal juices of geese does kill the nuisance, so small flocks were kept (indeed always had been but were confined in their wandering) and allowed to wander the pasture – a goose eats as much grass as one sheep – to clean it of the fluke.

In dry stone walled farmsteads a small low passage was built into the field boundaries to allow the geese to wander freely. These ‘creeps’ or ‘lunkies’ are similar to the larger and higher structures which allow sheep to pass through when required.

I will write about the activity of turning the fleece into usable wool later. For now that pretty much illustrates and explains the artefacts in the collection relating to the ubiquitous sheep.